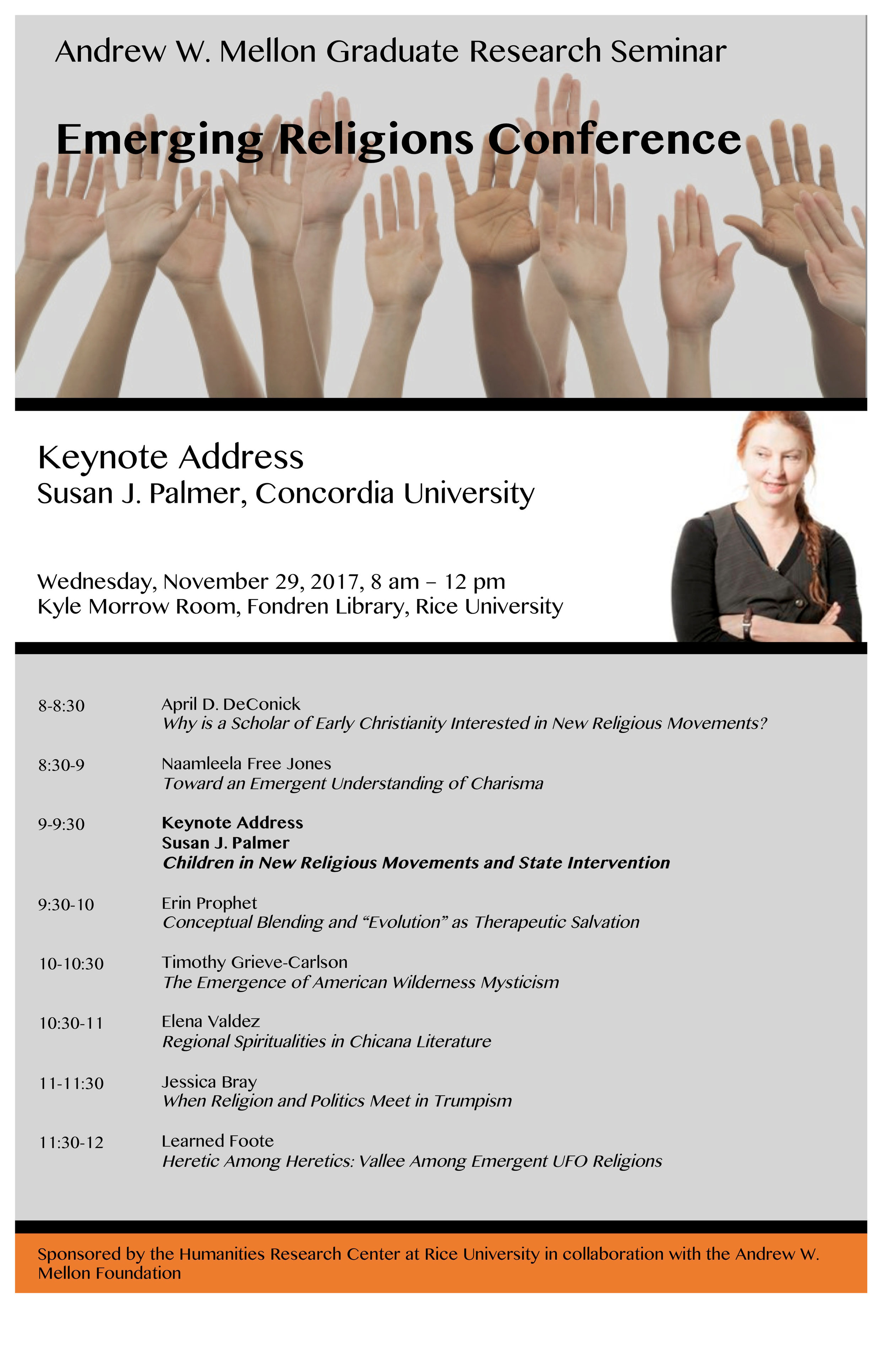

Emerging Religions Conference

/I forgot to post the information about our Mellon Seminar Conference. It happened yesterday, but was a great event featuring Susan Palmer as our keynote.

I forgot to post the information about our Mellon Seminar Conference. It happened yesterday, but was a great event featuring Susan Palmer as our keynote.

As we begin to prepare for the visit of Professor Mark Turner, a professor of Cognitive Science from Case Western Reserve, we have discussing the field of cognitive psychology. One book that particularly grabbed my attention this week is

Edward Slingerland (PHOTO from his webpage HERE)

,

What Science Offers the Humanities: Integrating Body and Culture

(2008).

I can't imagine writing a more courageous book than this, especially as a professor of ancient Chinese religion which is where Slingerland's training is. I was taken by the book for many reasons (and I am still processing it), but what struck me immediately was fact that he sees some of the same problems with postmodern theory that I do, and responds in ways similar to my own responses, responses which I have been recording on this blog, as I go about trying to develop a new sort of historical approach to the study of my texts. What I have come to realize over the course of this year is that I refuse to-throw-the-baby-out-with-the-bath-water. What is happening in my mind and through my pen (yes I still write with a pen) is a major remodeling and rebuilding of Tradition Criticism, in light of its postmodern crucifixion. I am developing an approach I am calling Transtradition Criticism. I will post more about this development later.

To return to Slingerland. He argues that postmodern theory has swept through the Academy, leaving us suspicious of any truth-claim and with "a conviction that the distinguishing mark of sophisticated scholarship is an ability to engage with a prescribed pantheon of theorists" rather than serious study of primary texts. What was fun at first "has left us with an intellectual hangover" (2008, 1), luxuriating in language for language's sake.

I couldn't agree more. In my opinion, we are stranded in a place of nowhere, immobilized by disembodied discourses, authorless and textless, outside of history. With nothing empirical, with no sameness, we are lost in a jumble of difference. We are left to describe what we see as ours, with no power to interpret beyond this. Even these meager descriptions are left in an ethical vacuum to be siphoned off and co-opted to support nefarious purposes.

The Humanities are dying and we are the ones who are responsible to save them.

The big question is HOW? Slingerland offers a solid solution. He says that we need to get our act together and learn from scientists how human beings operate, particularly as embodied cognitive beings. He demonstrates how humanists operate within outdated models of anthropology, and need to come to terms with the fact that science has discovered fundamental things about the human being. That we need to take embodiment seriously or be doomed to spinning tales inside of tales.

In Slingerland's words: "The fact that these body-minds are, have always been, and will always continue to be part of the world of things effectively short-circuits the epistemological skepticism that permeates postmodern thinking. A nondualistic approach to the person promises no privileged access to eternal, objective truths, but is based upon the belief that commonalities of human embodiment in the world can result in a stable body of shared knowledge, verified (at least provisionally) by proofs based on common perceptual access. By breaching the mind-body divide - by bringing the human mind back into contact with a rich and meaningful world of things - this approach to the humanities starts from an embodied mind that is always in touch with the world, as well as a pragmatic mode of truth or verification that takes the body and the physical world seriously" (2008, 8).

The seminar investigated ancient initiatory religions this week, trying to sort out the goings-on in Eleusis. I haven't thought hard about Eleusis and the Demeter rites for about twenty-five years, so it was pleasant to study that material in a more substantive manner this week.

I was very aware this time through the material of the attractiveness of the rites. I didn't find myself asking why someone would want to be initiated, a question that engaged me as a young person. Why would anyone want to haul a pig down to the sea, wash it and sacrifice it? Why would anyone want to parade for 12 miles from Athens to Eleusis, bringing the sacred objects with them and be mocked along the way? Why would anyone want to drink an unknown substance, eat BBQ, and then watch a drama of the emergence of Kore from the Underworld in a cave at night? Why would anyone want to tramp around in mud, lead by hand in the dark, only to be blinded by light and then shown a grain of wheat in a basket? And to do this twice?!

Other than the fact that this sounds to me now more like a big party and a haunted house escapade than it did twenty-five years ago, I think my age is catching up with me. Because now I see the death aspect even more prominently. If I were part of a culture that taught that Persephone, the Queen of the Underworld, emerges every year in a cave in Eleusis, and that if I went through the rites, I would visit the Underworld and meet Persephone and Demeter so that when I die I would have a wonderful afterlife, I would have been the first person in line. To think that this journey was performed, so that initiates felt that they had actually experienced the journey through Hades and met the gods, well that is attractive beyond measure. I would have felt like I had faced death and conquered the unknowable, so that my life could be lived even more fully.

An experience like that breaks down human culture into a few startling breaths: to be human is to die; to be human is to live in the face of our death.

Is human culture our response to the knowledge of our mortality? Not just religion, but everything we have produced, everything that makes up human culture as Jan Assmann says in his book

Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt

?

I want to end with three quotes:

"Happy is the one who having seen these rites goes below the hollow earth, for that one knows the end of life and its god-given beginning." Pindar, Fr 137a

"Three-times blessed are those mortals who have seen these rites and thus enter into Hades. For them alone there is life. For the others, all is misery." Sophocles Fr 837

"The Ninetieth Psalm prays, 'Teach us to count our days, that we may gain a wise heart.' 'To count our days' means to hold each day dear, knowing that life is finite. The days derive their value from their end; since we must die, we 'count' our days. Death gives life its value, and wisdom consists in being aware of this value." Jan Assmann,

Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt

, 8.

This is day 17188 for me.

I spent last week reading older materials published in the early 1900s and then in the 1960s about rites of passage (life crisis, induction, and calendrical rites). I found the material exhilarating. I went back to Arnold van Gennep who wrote a book in French in 1908,

The Rites of Passage

. I found the work to be very complex and thought-provoking which I wasn't expecting. The experience makes me even more determined to study materials written before 1960 (or some might even say 1980). Just because we have learned some things since then, doesn't mean that the older studies have no value or that their methodological approaches are empty.

I also learned that we need to reread these materials because their reception history in secondary literature has misread or devalued the original material in such a way that the secondary discourse no longer is faithful to the old author. For instance, in van Gennep's work, I found very complex and nuanced thinking, far more than contemporary references to him grant him. His biggest 'receiver' was Victor Turner who famously studied the 'limen' or state of marginality that novices-intitiates find themselves in when going through rites of passage. Turner refers again and again to van Gennep in one brilliant essay after another, crediting van Gennep with the idea that rites of passage are characterized by three stages: a stage of separation from normalcy; a stage of liminality or marginality; and a stage of aggregation into normalcy restructured.

Van Gennep does say this, but not quite as directly as we are led to believe. He, in fact, nuances it substantially. First he analyzes these three, not as stages or phases, but as three kinds of rites of passage, thereby subdividing rites of passage into rites of separation, transition, and incorporation. He explains that these types of rites of passage are not developed to the same extent by all people in every ceremonial pattern. Rites of separation are prominent in funeral ceremonies, rites of incorporation in marriages, transition rites in pregnancy, betrothal and initiation. He says, "Although a complete scheme of rites of passage

theoretically

includes preliminal rites (rites of separation), liminal rites (rites of transition), and postliminal rites (rites of incorporation), in specific instances these three types are not always equally important or equally elaborated" (11).

He also understands that rites of passage may include other forms of rites. Marriage ceremonies might also include fertility rites; birth ceremonies might also include protection and divination rites; etc.

At any rate, these examples serve my point today. Secondary discussions of authors, particularly older authors who wrote before 1960, work to homogenize the author and simplify his or her contribution. Then they can more easily be attacked for what they didn't do (even if they in fact did!). When I read van Gennep, I found his work to be very aware of the problems of classification and the acknowledgment of historical complexity and specificity. We can learn much from him still.

This week we took an excursion into the development of American metaphysical religions. I am particularly interested in the ways in which scholars have tried to tell the story of the creation of the modern New Age. If you are interested in this topic, I recommend a couple of books that provide very good historical overviews. The first is

The Western Esoteric Traditions

. Not only is the picture on its cover one of my very favorite woodcuts from the Renaissance, but the book carries the reader through all the esoteric streams in an historical journey. The other book, which I found stunningly well-researched and written is by

Catherine Albanese (pictured here),

. So I have chosen to share some of the insights I brought away from her work.

What Albanese does methodologically is fascinating. What she appears to me to be doing is creating a sweeping picture of each century by laying out the vast networks of ideas and information and practices happening simultaneously. She suggests that the traditions she is investigating are interacting

within

each other rather than with each other, so that she comes to understand the modern New Age as expansive and combinative, a religious phenomenon that is an amalgamation of any number of esoteric trajectories, including Hermeticism, Transcendentalism, Spiritualism, Mesmerism, Swedenborgianism, Christian Science, New Thought, Theosophy, Asian religions, Native American religion, and Quantum physics. She characterizes the New Age as a vast cultural sponge that absorbed whatever spiritual moisture was available. So it represents a grand ecumenicity. The New Age represents a fluid form of community available through networks and networking. This results in different levels of affiliation and commitment from fully-engaged service providers and strong followers who show up a workshops and other events to serious part-timers and causal part-timers or nightstand followers who read occasional books, and attend infrequent lectures. Members have often crossovered from traditional religions, seeking experiences considered by them to be more spiritually engaged.

She describes the themes of the New Age, and other metaphysical traditions, as emphasizing the power of the mind, a worldview of correspondence and connection between the spiritual world (the real world) and the physical (a transitory world), a preoccupation with summoning energy from on high to 'save' the human situation, and healing what was humanly amiss. These are the core beliefs and practices.

After reading her book, I am convinced that American metaphysical religion is one of three forces in American religion from the beginning, along with the mainstream traditions and evangelicalism. I am also convinced that the ancient Gnostics I study weren't so different from modern New Agers, with the exception that they did not get good press behind them like the New Age movement did. Remember Shirley MacClaine, her movie and books?

The New Age movement, with the hungry media behind them, was able to make exoteric what had previously been esoteric. And it has had a lasting impact on American culture. Yoga has become mainstream, along with beliefs in reincarnation and discussions of karma. ESP and UFO are abbreviations we all share, whatever our convictions about them might be. Psychics are consulted to assist police investigations, astrology made it into the Whitehouse, alternative medicine is practiced alongside traditional western medicine, all without too much discomfort. Ecology and healthfood is now mainstream. How many of us have yogurt in our lunchboxes?

The seminar examined New Historicism for the past two weeks. Contrary to its title, New Historicism is not a method created by historians writing histories. It emerged from literary criticism among professors of Renaissance literature who were trying to illuminate literature with reference to historical sources and intertextuality investigating what Greenblatt (the originator of the approach and pictured here) calls Cultural Poetics. This approach developed in critic of New Criticism, not old-school German Historicism and Positivism. New Criticism is the common approach to literature with reads it ahistorically, focusing on single texts as enclosed units of narrative and imagery.

New Historicism or Cultural Poetics tries to examine the text in its context, while also asking how the text enforces the cultural practices that it depends on for its own production and dissemination. In this way, these critics draw attention to the processes being employed by contemporary power structures, like the chuch, state, and academy, to disseminate knowledge. They explore a text's historical context

and

its political implications, and then through a close textual analysis they note the dominant hegemonic position. New Historicism or Cultural Poetics is a politicized form of literary criticism with an eye toward historical contextuality. It is grounded in the critical theory of Foucault, the work of the Cultural Materialists, and anthropology of the variety espoused by Clifford Geertz who advocated writing "thick descriptions" of culture that explains human behavior within particular contexts rather than merely as part of symbolic systems.

After reading deeply into this scholarship, I really feel that New Historicism has a political mission. These critics are all about critiquing capitalism and market relations, and in my mind, retrofitting that critique back onto historical sources. So what they write often appears anachronistic, that is, bringing our contemporary values to play in the past. To their credit, they are aware of this, and so are willing to admit it in their analyses.

To do this, they read all literature and artifacts side-by-side with no distinction, mining what they call the cracks, slippages, fault lines and absences in the traditional historical narratives. While their willingness to eliminate canonical boundaries is to be applauded, I am less thrilled that they do not generally evaluate the differences in the media they examine. Various forms of materials were created with difference purposes and different intent, and what any of it can tell us about anything must be weighed carefully. A letter fragment and a gospel, for instance, are not the same thing. A masterpiece painting and a magical drawing in a recipe book are interesting, but they are not giving us similar information. What either might tell us needs discussion.

While I found much of their work stimulating, I was left a bit puzzled. How "new" is any of this? Historians have been dealing with cultural context, artifacts, and multiple texts for, well, forever. In religious studies, we have been dealing with breaking down canonical boundaries for over fifty years, and we have been discussing power relations and political agendas for at least as long. The differences are that historians are interested in getting at the meanings of the literature they are examining, and we want to investigate the politics of the time of the texts. New Historians are interested in exploring the various discourses that inform the literature they read, and are more motivated by contemporary politics which they think is somehow reflected in these discourses (in ways similar to the ideas of queer theorists or feminist theologians).

Post-modernism and Post-colonialism were the subjects of the theory discussion this week. We characterized Post-modernism as "the collapse of the Grand Narrative" and Post-colonialism as "the writing of the 'Other'". One book that we reviewed was Lyotard (pictured),

The Post-Modern Condition

(1979) where the term was coined, 'post-modernism', to refer to the incredulity of the meta-narratives constructed by societies (how we can know everything through science; that we make progress in history; that there is absolute freedom; etc.). He points out how inadequate our big stories are, because they do not encompass us all. He is particularly critical of our commonly held narrative that knowledge must be efficient in order to be valuable. Thus if we can't prove that a certain type of knowledge is efficient or useful, it is pushed aside and we feel terror.

We highlighted the discourse of the Humanities in this light. The Humanities, because it does not offer efficient or useful knowledge, has lost its voice in the discourse of knowledge that pervades our society, particularly the scientific discourse. The discourse of knowledge that we are familiar with today is no longer a discussion of "is it true?" but "is it useful?" and "is it saleable?" Knowledge has become a commodity.

I keep thinking about our public education system and how much this discourse of knowledge has negatively impacted it. We now want teachers to give knowledge to the students like it is a commodity or good that can be exchanged, and

make

the student learn it. We judge whether or not this exchange has occurred by testing students and then tying teachers' jobs and salaries to their students' academic performance. The problem is that all knowledge is not a commodity, nor is all knowledge useable. And learning is not a contractual business exchange. While teachers have a responsibility to teach well, students and families have the responsibility to commit to learning even non-usable or non-applicable knowledge. Students' are responsible actors too. They are participants of power in their education.

Lyotard and other philosophers highlight two main discourses of knowledge: 1. the scientific discourse (efficient knowledge); 2. Narrative (non-efficient) knowledge. Lyotard also acknowledges the "sublime" which is knowledge at the edges of conceptualization, that can not be formulated via faith, imagination, or reason.

The post-modernists suggest that we set aside the metanarratives and focus on the fragmented stories or micro-narratives; that we live with a series of mini-narratives that are contemporary and relative. While truth doesn't disappear, it must be recognized as fragmentary. They call this fragmented truth "difference" so that knowledge becomes "difference". They do not want to understand difference as negative, as in "what it is not" (a cat is a cat because it is not a dog). What they want to say is that we are the ones who assign similitude to things; in reality there are just differences (a cat is a cat and a dog is a dog and they are different).

All of this raises a series of questions for me. While I am delighted to work on fragmented stories of the past, as a historian of 'heretics', I also must construct and operate from a larger narrative that makes sense of that past. I do not see unity as the enemy, nor do I see difference as the saint. We as human creatures are wired for narrative. Our brains work in such a way that we constantly construct unity from our own life's fragments, as we also construct differences. I would characterize humans as "comparativists" who understand unity and difference in relationship to each other. Narratives are necessary, even Grand ones, or life would be chaos for us all. So while the different must be embraced by the historian (and not judged negatively), the discussion of unity is still necessary. Any unity that is constructed must be reasonable and fair, one that accounts for the micro-narratives while also accounting for the practical course of history and the relationships between people and groups.

Our theoretical topic this week has been Social Memory Theory, which developed out of the 1925 work of Maurice Halbwachs,

On Collective Memory

. Halbwachs was not interested in social memory (the memory shared by a group or society) but rather was arguing that the individual's memory was shaped by society, and he wanted to know how. Decades later, in the 1970s, his idea that memory and society are bound up was applied substantially to historiography and the study of modern social memory began to flourish in intellectual circles.

The foundational premises of social memory theory are:

1. Memories are products of the present and not the preservation of the past.

2. Memories are ignited and limited by social frameworks.

3. Memory distortion is the difference between the memory of the past and the past actuality.

4. All memory is distorted or refracted.

This knowledge makes the work of the historian interesting. There are a range of opinions among social memory theorists regarding whether or not it is possible to recover the past actuality from memories, and if so, how much. My own work as a historian has been deeply affected by social memory theory which I openly embrace. It has shifted my self-understanding as a historian. I no longer worry about recovering the undistorted past because I am not convinced I can do this with the sources I have to work with. The questions I try to answer have dramatically shifted. What I want to know now is how and why particular groups remember their past in certain ways, and how and why counter-memories of the same event develop. I am particularly interested in what I call "iconic" or "memorial" representations of individual and events, as providing insights into the group's self-understanding. Studying these allows me to reconstruct the earliest memories of the individual or event, and come to some understanding of how and why groups developed in the directions they did.

This doesn't mean that the memories don't point back to some past actuality. It just means that recovering the past actuality is nigh impossible. What I am better at doing is recovering a scenario of historical plausibility based on the memory sets available for study. I am convinced from my work in memory and how groups handle their past, that historians are actually assisted in this task by three dynamics of memory:

1. Although invention or fabrication is possible (as in the case of new governments trying to legitimize themselves), social memory is largely a subconscious or unconscious operation. It functions by selecting something important from the environment and putting it within the mental frameworks that exist in our minds and then relocalizes them within our present experience. Schwartz has noted in his work on Lincoln again and again that many of our heroes today are selected to be heroes because there was something that they did that made us see them as heroic in the first place.

2. Memory (whether individual or social) is limited by society. What is remembered has to be plausible and make sense to the group and what it already knows about its past. In other words, it is conservative even by society's standards, and builds incrementally and with continuity between the past and the present.

3. What we can see in our sources are the effects of the what actually happened, so by studying the effects, it is possible to create scenarios of historical plausibility that would best explain them. Here I am convinced that counter-memories are very significant (thus my intense work on the marginalized or forbidden memories): both the counter-memories created within the group and among different groups. We can not just study the similarities. It is the differences that reveal the full story!

There are many great books on social memory application. If you are interested in how social memory theory might be applied to the quest for the historical Jesus, I recommend Anthony Le Donne's recent book,

and now his trade book on the subject,

The Historical Jesus: What can we know and how can we know it?

which will be released in January. Great reading!

This week we spent reading classic anthropological ethnographic studies on death. I was assigned

Consuming Grief

by Beth Conklin. It is about the Amazonian Wari' and their pre-contact funerary rituals which centered around eating the body of the deceased. Conklin wanted to know why they practiced funerary cannibalism and so she spent years among the Wari' recording family histories of all of them. Since funerary cannibalism is no longer practiced, she had to rely on memories of the Wari'. Apparently this is a 'no-no' in anthropological method, because she was not able to observe the ceremonies directly herself, so she wasn't able to draw her own conclusions from those observations.

This made me laugh aloud since all I do is work from secondary materials, having no direct contact with any early Christian (and I am completely jealous of Conklin who could talk to people who were there!). What disturbs me about the anthropological method is the fact that anthropologists seem to think that their own observations and interpretations of the materials are in some way superior to what the people they study remember and tell them. Conklin was trying to swim upstream, making the very fundamental argument that we have to start listening to the people we study. Maybe they know what they are talking about. She finds it essential to take seriously what the Wari' themselves say about their cannibalism. She writes: "The problem with limiting analysis to the level of ideas and symbols, as many anthropological studies have tended to do, is that this leaves out the very aspects that Wari' themselves emphasize: cannibalism's relation to subjective experiences of grief and social processes of mourning."

Why did the Wari' cannibalize their deceased? Because it helped the deceased transition into the spirit world to join the realm of the animal spirits who dwelled there, and it aided the grieving family disassociate from the deceased and forget them. It was part of the blotting out of their memory that also involved burning the home and property of the deceased, and never using their name again. One of the elders said to her, "Why are you always asking about eating the ones who died? You talk about me eating; Denise [Merieles, a Brazilian ethnographer] came here and asked me about eating. The missionaries and the priests always used to say, 'Why did you eat people? Why did you eat? Eating, eating eating! Eating was not all that we did! We cried, we sang, we burned the house, we burned all their things. Write about all of this, not just the eating!" (p. xxii).

I won't spoil the book for those of you who want to read it, but I want to end this post with an observation. Since the 1960s after contact with outsiders, the Wari' no longer cannibalize their dead. With contact brought infectious diseases that decimated their population. The missionaries, desperate to get them to alter their funerary ritual, told them that if they continued to eat the dead bodies, they would become infected with the disease. So the Wari' began to bury their dead as the missionaries wanted them to, even though they considered the ground to be filthy and polluted and cold, and still complain about their loved ones having to rot in the cold earth.

But all of this has me thinking about Christianity and those missionaries and us today whose central religious ritual is the killing and cannibalization of Jesus' body on an altar. The ancient Romans, in fact, accused the early Christians of just this crime. For Catholics, the bread and wine are transmuted into the body and blood of Jesus and are shared and ingested communally. For Protestants, the cannibalization is more symbolic, but nonetheless present.

Are we dealing with a matter of perspective? Who are the cannibals?

In seminar this week we discussed Religion and Psychology, the Psychology of Religion, and Psychology in Dialogue with Religion. And of course Jung was prominent. One of the readings was his book

Aion

, which is an unbelievable ride through Jung's mind and ancient Gnostic sources (quoted from the original Latin and Greek patristic sources). Unlike Freud, Jung thought that the human psyche is by nature religious and that the journey of the transformation of the self (a process he calls

individuation

) is at the "mystical heart of all religions." He felt that life has a spiritual purpose, a meaning beyond material gain and goals. He writes, "Our main task is to discover and fulfill our deep innate potential, much as the acorn contains the potential to become the oak."

This transformative process involves the integration of the person's consciousness with the unconscious in order to stave off unhealthy psychic tendencies such as repression, projection, etc. Jung talked about this process in terms of the union of opposites, including the ego-personality with its shadow. He was particularly fond of the Gnostic mythology which proved to him the accuracy of his theories, for erupting in their mythology was the religious equivalent of his psychological descriptions. For instance, the Gnostic myth of a Father without quality of being who is unknowable, is the unconsciousness. He quotes Epiphanius: "In the beginning the Autopater contained in himself everything that is, in a state of unconsciousness." This manifests or becomes conscious through the generation of the Christ who represents for Jung the perfect human self.

The book reads as a set of psychological sermons filled with esoteric references from ancient sources. Although Jung tries again and again to suggest that "psychology is not metaphysics", it is hard to believe him when faced with a volume this saturated with Christian ideas that are attempting to explain a three-year period when Jung believed he encountered the unconsciousness and lived to tell about it.

I am not sure that psychological models are going to assist me in my own historical work, except that Jung may be a very interesting figure to investigate as a mystic in his own right...as someone who took his personal experiences and the ancient Gnostic mythology and rewrote them as a modern psychological theory. Especially now that

The Red Book

is published.

This week we studied some of the structuralists and post-structuralists. One of the effects of these 'movements' is the promotion of the claim that the author of the text is of little or no consequence. Roland Barthes called this "the death of the author." He and others located the meaning of the text in the audience or reader, and thought that the quest for authorial intent was at best secondary, but in fact useless.

Being the pragmatist that I am, and an author myself, I find this proposal (as 'sexy' as it is) to be untenable. There are authors, and authors have intent, they write for multiple reasons, and they each have very specific cultural and historical contexts which are all over the things they write. It is possible to retrieve this information, although it must be done critically and carefully.

That said, I also want to say that it is equally true that meaning becomes the possession of the possessor. The text, once 'published' takes on a life of its own, and interpretations develop that may or may not have anything to do with authorial intent. These ways of reconceiving the text over and over in historical time belong to communities of people, and their view of the text reflects their own culture, history, memory, and crises. They also reflect interactions with others who are using the same text, although with differences of opinion about what it might actually mean.

I also want to emphasize that there is not necessarily a disjuncture between authorial intent and the first interpretations of the text that might exist. For some reason we have assumed that there is, seeing the early interpretations of the text as 'late' when compared to the author, and therefore of no consequence to our understanding of the composition of the text itself. Being a writer myself, I really question this. When I write something it is being written as part of a conversation that already is in play. So I am not originating the discourse. I am participating in it and am hoping to influence it. So instead of assuming a complete rupture between what is written and the first interpretations of it, perhaps we need to explore the earliest conversation about the text and investigate how what is written fits into it?

I know. This is different, very different. It is different from the usual approach which has attempted to give meaning to the text as modern people read and impose that meaning, so we have ended up with mainstream accepted interpretations of Paul or Mark or John that are nothing more than reflections of post-reformation theology. And these are posited as the author's intent. And the ancient conversation about the text is ignored as secondary and irrelevant. What is backwards here?

Even though I don't agree that the author is dead or secondary in the field of meaning and interpretation, I close with a quotation from Barthes which impressed me as gorgeous in its acknowledgment of the reader's power, a fact we must integrate into our new historicism (for which I yet have no name).

"We know that a text does not consist of a line of words, releasing a single 'theological' meaning...but is a space of many dimensions, in which are wedded and contested various kinds of writing, no one of which is original: the text is a tissue of citations, resulting from the thousand sources of culture...In this way is revealed the whole being of writing: a text consists of multiple writings, issuing from several cultures and entering into dialogue with each other, into parody, into contestation; but there is one place where this multiplicity is collected, united, and this place is not the author, as we have hitherto said it was, but the reader: the reader is the very space in which are inscribed, without being lost, all the citations a writing consists of; the unity of a text is not in its origin, it is in its destination; but this destination can no longer be personal: the reader is a person without history, without biography, without psychology; he is only the someone who holds gathered into a single field all the paths of which the text is constituted."

The topic for the second discussion in the

mellon

seminar was Ritual Theory. The readings were numerous, and it was fascinating for me to spend a week going over the history of the discussion of ritual and myth. I realized even more than I had before how much the question of the relationship of ritual and myth has defined the field of religious studies. I'm not so sure it ought to have, but we are stuck with the fact that it did. If you are looking for a very well-written detailed overview of the history of ritual theory, I recommend the first three chapters of

Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions

.

I am not going to go into detail here about the history of ritual theory. What I am going to do is reflect on my own understanding of ritual. It is not an understanding that came out of studying ritual theory, nor trying to negotiate the Myth and Ritual School or the views of Durkheim or Freud. My reflections come straight from my work as an historian who has immersed herself in ancient texts for the last twenty-five years of my life. I have discovered that I tend to be very pragmatic in my approach.

1.

Ritual and myth have a symbiotic relationship.

There is a connection between the community's ritual and myth, although these connections are not stable. Both ritual and myth shift in their performance and narrative over time and for various reasons, some conscious and some not. It may not be possible to determine whether the ritual or the myth came first in the formation of the movement. For me this is not even the interesting question. The interesting question is how and why the ritual and myth shape and reshape each other in peculiar ways.

2.

There is a community of real people involved in the ritual and the myth.

The texts I study are about practices and ideas that involved real people in real life situations. The category "

intertextuality

" is something that was made up so that the problem of real communities and their shape or historical boundaries can be ignored.

3.

Ritual and myth are culturally-determined and historically bound.

We might be able to find some psychological or cognitive feature in humans that predisposes us to create rituals that involve stages of separation and reintegration, but the quest for 'a universal myth' or 'a universal

ur

-ritual' behind all myths and rituals is not tenable, at least from the perspective of a historian.

4.

There are different types of rituals and myths, and therefore different functions.

Rituals and myths of initiation may not have the same function as rituals and myths of matrimony, birth, or purging. While the main function of one ritual might be to foster social cohesion, another might be to relieve personal guilt or anxiety. So a careful mapping must be put into place and universalism avoided.

5.

Rituals and myths build and support relationships of power within the community.

They provide divine sanction and legitimacy for the dominance of some and the subordination of others.

6.

When the ritual and myth of the dominant group does not answer all the questions or is contradictory, supplementary and alternative rituals and myths are developed, sometimes

clandestinely

.

And here lies the origin of the concept of orthodoxy and heresy.

Isla Carroll and Percy E. Turner Professor of New Testament and Early Christianity since 2006

Chair of the Department of Religion at Rice University 2013-2019

Figure Foundation Book Award for The Gnostic New Age: How a Countercultural Spirituality Revolutionized Religion From Antiquity to Today (New York: Columbia University Press 2016)

Grant Recipient with James McGrath and Charles Häberl, National Endowment for the Humanities, The Mandaean Book of John: Critical Edition, Translation, and Commentary, 2012-14

Co-Founder and Executive Editor of GNOSIS: Journal of Gnostic Studies (Leiden: Brill) since 2015

Editorial Board of Journal of the American Academy of Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press) since 2019

Editorial Board for Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies (Leiden: Brill) since 2008

Grant recipient and Faculty Leader of Andrew W. Mellon Graduate Research Seminar, Emerging Religions 2017-2019

Chair, Society of Biblical Literature, Committee for the Status of Women in the Profession, 2016-2018

Research Fellow in the Boniuk Institute for the Study and Advancement of Religious 2014-2015

Associate Editor for Macmillan Interdisciplinary Handbooks on Religion, ten-volumes, 2016

Faculty in the Center for the Study of Women, Gender and Sexuality, Rice University, since 2006

Grant recipient and Faculty Leader of Andrew W. Mellon Graduate Research Seminar, Mapping Death, 2010-2012

Associate Editor for Vigiliae Christianae, Journal and Monograph series (Leiden: Brill) 2014-2015

Co-chair of Nag Hammadi and Gnosticism Section, Society of Biblical Literature, 2012-2018

Founding Chair and Member of Steering Committee of Mysticism, Esotericism and Gnosticism in Antiquity Section, Society of Biblical Literature since 1996

Member of Committee on the Status of Women in the Profession, Society of Biblical Literature, 2012-2018

Founder of the Cognition and Culture in the Humanities Workshop, Rice University, 2011-2013

29th Annual Loy Witherspoon Lecturer, University of North Carolina 2013

Centennial Lecturer for Rackham School of Graduate Studies, University of Michigan 2012

Edgar and Dorothy Davidson Annual Lecturer, Carleton University 2009

Member of Phi Kappa Phi Honors Society since 2002

Member of Phi Beta Kappa Honors Society since 1988

Affiliated with the Society of Biblical Literature since 1987

Affiliated with the International Association for Coptic Studies since 2006

Affiliated with the North American Patristics Society since 2006

Affiliated with the American Academy of Religion since 2007

Affiliated with the European Society for the Study of Western Esotericism since 2016

C

Powered by Squarespace